Jeremy Bentham's Body Has Had One Of The Strangest Afterlives In History

Born in 1748, Jeremy Bentham was a 19th-century English philosopher, economist, and social reformer. Bentham had interesting ideas about mortality and mourning, which shaped how he wanted his remains handled after his passing. By Bentham's request, his preserved body was on public display and used for instruction.

Bentham adopted and followed a practical life philosophy - he aimed for usefulness even in the afterlife. The reality of what happened to his body after he passed in 1832, however, wasn't quite what he intended. Bentham's remains, especially his head, took on a fascinating, if not horrifying, transformation.

He Wanted His Body Rolled Out At Parties

Photo: Philafrenzy / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0Bentham decided he didn't want to remain, as he put it, "altogether useless" after his passing, and came up with the concept of the auto-icon. Bentham envisioned the auto-icon as an accessible body ready for someone to wheel out at parties upon request.

Bentham hoped by preserving his body, his friends could still see him and may feel inspired to donate their bodies for similar purposes.

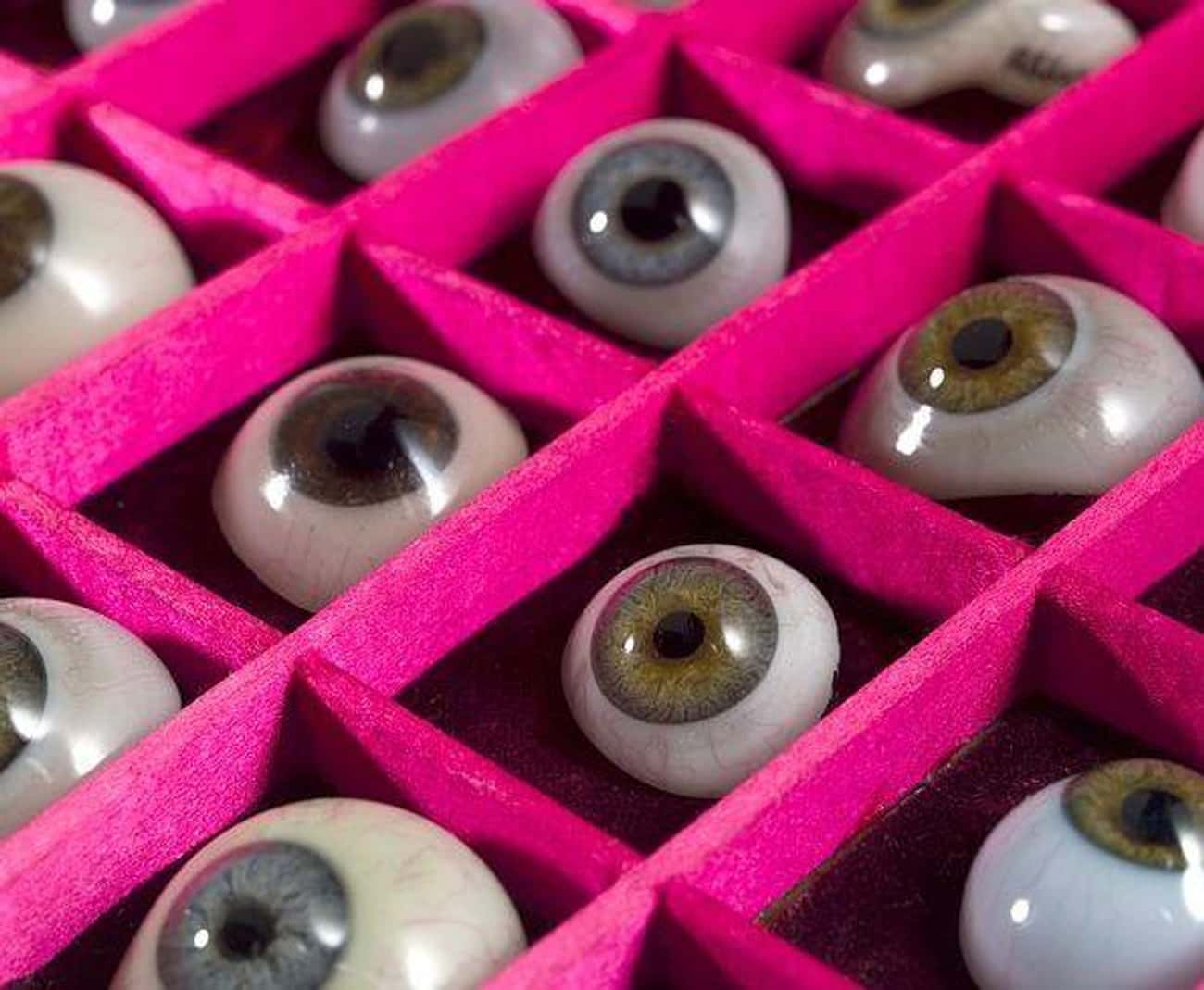

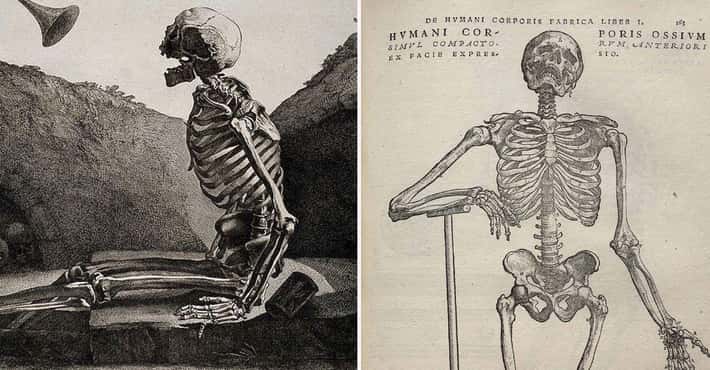

He Carried Glass Eyes In His Pocket For Insertion Into His Preserved Head

Photo: Wellcome Images / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 4.0From an early age, Bentham knew what he wanted to happen to his body after he passed: He wished for someone to dissect, embalm, and display his body as a model for the world to see. As he came closer to the end, Bentham grew increasingly focused on the specifics of his impending mummification and display. He allegedly carried a pair of glass eyes with him during his final decade of life for easy insertion into his head when his body was on display.

Bentham perished on June 6, 1832, at the age of 84. He tasked Dr. Thomas Southwood Smith with fulfilling his wishes.

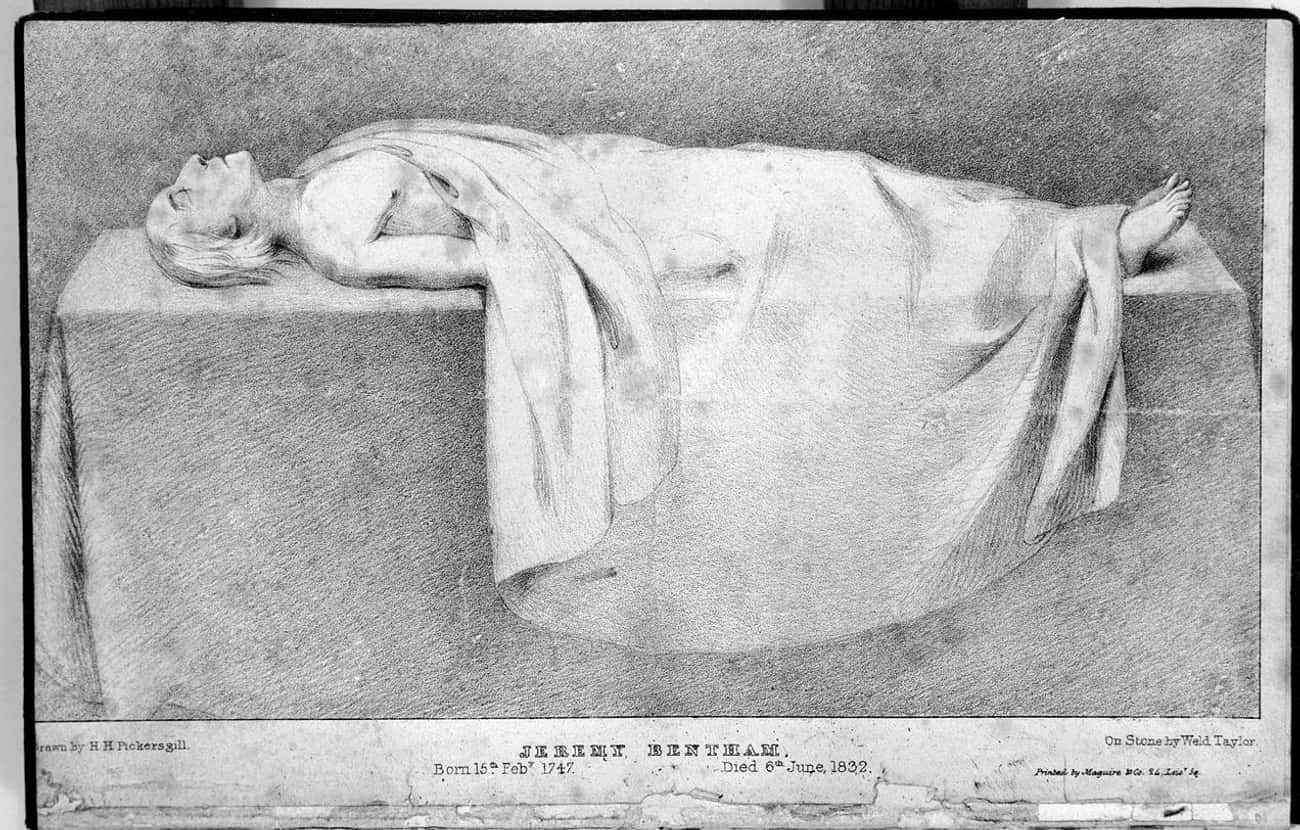

He Was Dissected In The Presence Of His Friends

Photo: H. H. Pickersgill / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 4.0Three days after Bentham's passing, Dr. Smith dissected his body, as instructed, during an anatomy lecture. Bentham's closest friends received invitations the day before, which read:

It was the earnest desire of the late Jeremy Bentham that his body should be appropriated to an illustration of the structure and functions of the human frame. In compliance with this wish, Dr. Smith will deliver a lecture, over the body, on the usefulness of the knowledge of this kind to the community. The lecture will be delivered at the Webb-Street School of Anatomy and Medicine, Web-Street, Borough, tomorrow, at 3 o'clock; at which the honor of your presence, and that of any two friends who may wish to accompany you, is requested.

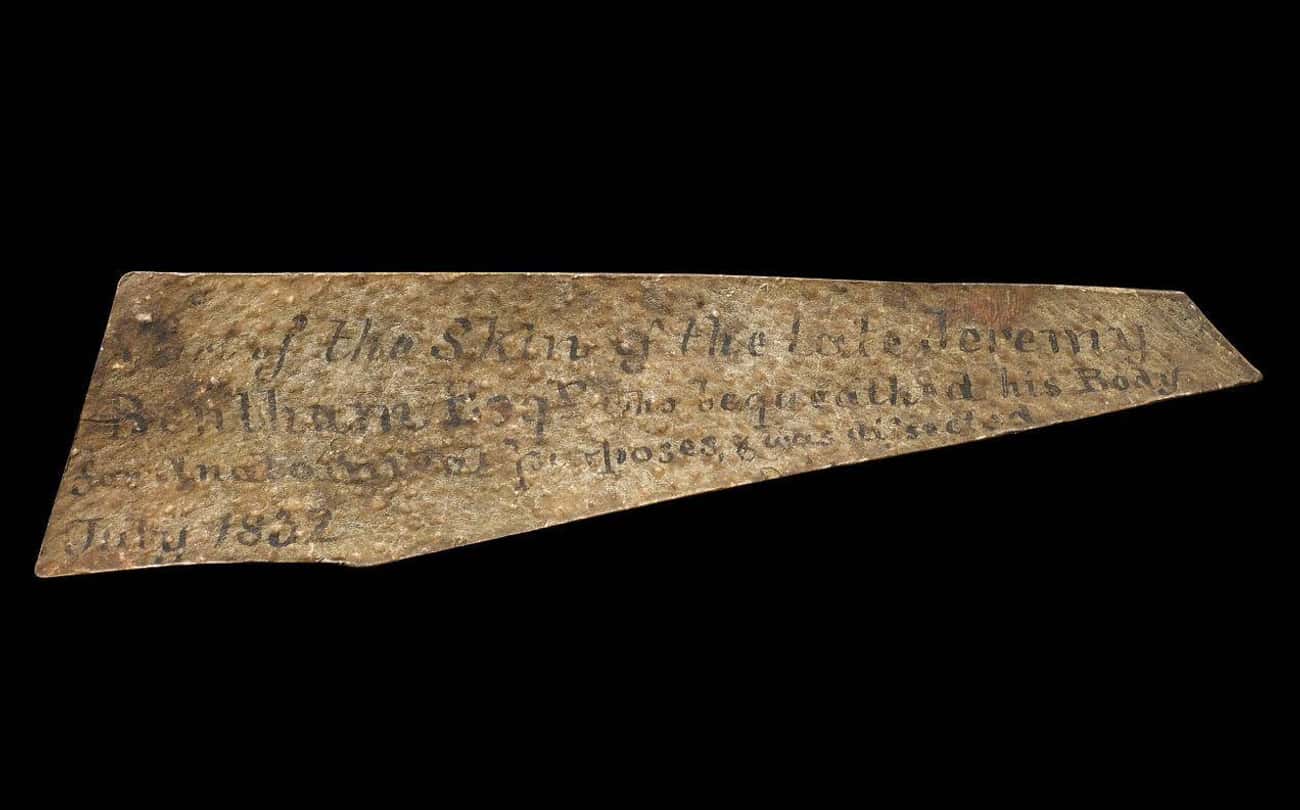

The Doctor Cut Him Open In The Interest Of The Greater Good

Photo: Wellcome Images / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 4.0In addition to Bentham's friends in attendance, the dissection audience included noted medical professionals, philanthropists, and several members of the government. Autopsies and the study of anatomy were controversial at the time.

Dr. Smith allegedly said to the onlookers at Bentham's dissection, "If [...] I can promote the happiness of the living, then it is my duty to conquer the reluctance I may feel to such a disposition of the dead, however well-founded or strong that reluctance may be."

His Skeleton Was Put Back Together, But There Was A Problem With The Head

Once the dissection was complete, Dr. Smith stripped Bentham's body of its flesh. He reassembled the skeleton but left the head detached. The preservation had unexpected results - Bentham's head looked leathery and gaunt rather than maintaining its form.

Dr. Smith wrote about the process:

I endeavored to preserve the head untouched, merely drawing away the fluids by placing it under an air pump over sulfuric acid. By this means, the head was rendered as hard as the skulls of the New Zealanders; but all expression was, of course, gone.

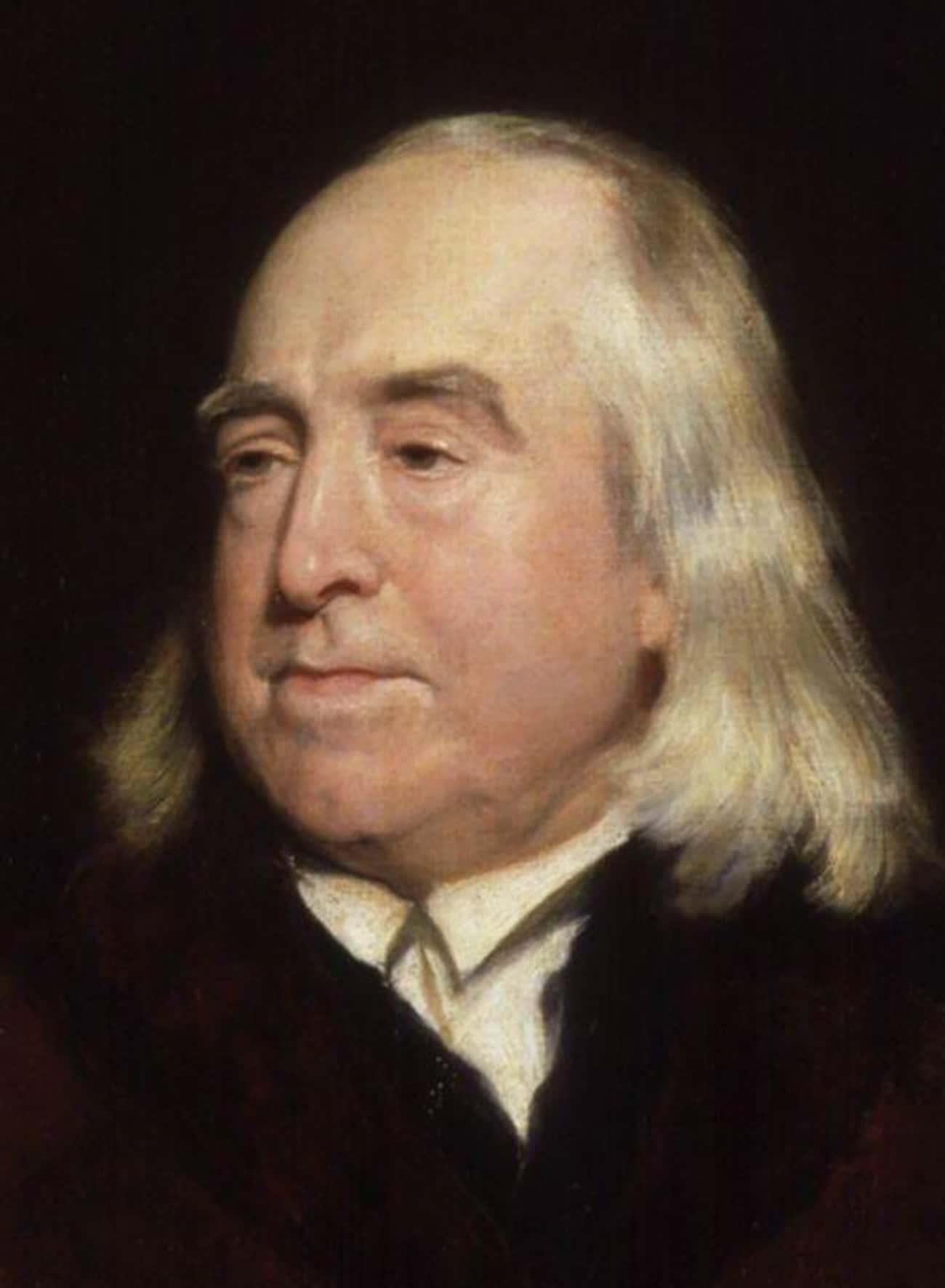

His Head Looked Too Unlike Him, So The Doctor Commissioned A Wax Substitute

Photo: Henry William Pickersgill / Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainDespite Dr. Smith's efforts to keep Bentham's head well preserved, his methods proved ineffective. Thanks to the sulfuric acid, Bentham's head was too discolored and misshapen to remain on his body. As a result, Dr. Smith commissioned a likeness of his friend in wax.

French artist Jacques Talrich used a bust of Bentham, a portrait by Henry Pickersgill, and a mourning ring adorned with Bentham's profile as guides while sculpting the new head. Talrich was known for his anatomical models, and, according to Smith, created "one of the most admirable likenesses ever seen."

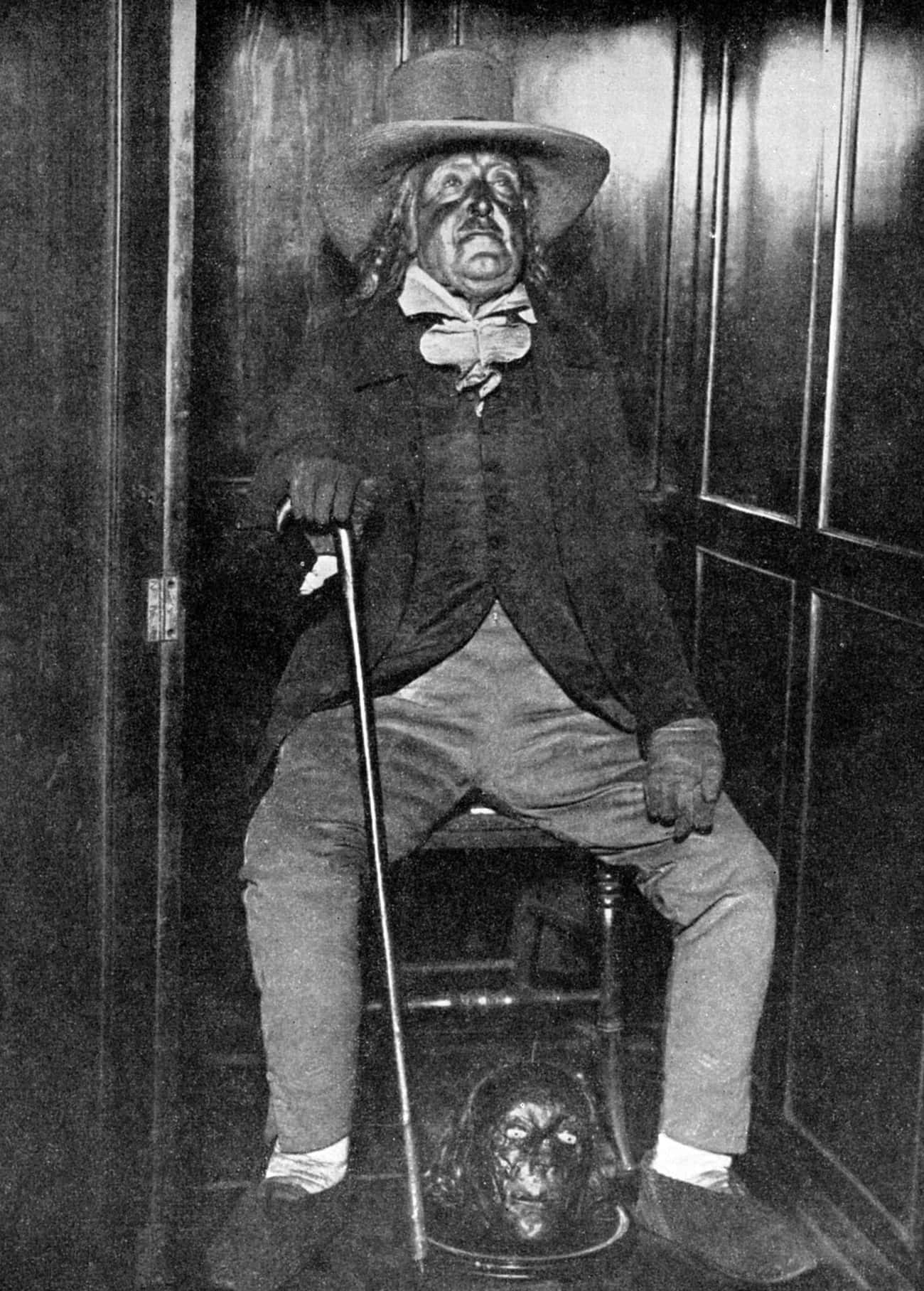

His Real Head Sat At His Feet Until It Was Deemed Too Disturbing

Photo: Print Collector/Contributor / Hulton ArchiveThe finished wax head rested on top of Bentham's skeleton. Dr. Smith arranged Bentham's body, adorned in a black suit, inside a glass and mahogany case. At first, Bentham - who posed "seated in the chair" and "[held] the walking stick, which was his constant companion when he was out, called by him Dapple" - was placed at Dr. Smith's house.

The display was too big for the doctor's home, however, so he donated Bentham's body to University College London. At the university, the display had Bentham's disfigured head between the body's feet, where it remained until 1975.

His Head Was Stolen And Held For Ransom In The 1970s

In 1975, a group of students at University College London stole Bentham's head and demanded the university donate £100 to charity. The school's response was a £10 donation; the students caved and returned the head to the school unharmed.

In a series of continued pranks, students pilfered the head for various purposes. It was purportedly used as a soccer ball on one occasion, and later students from the school's rival King's College stole it. The university removed the head from the case to prevent further theft.

His DNA Is Being Tested For Asperger's And Autism

Because it showed signs of deterioration, researchers transferred Bentham's head to the UCL Institute of Archaeology's climate-controlled storeroom in 2002. The department pulls the head out for special occasions, and checks on it regularly to make sure more hair has not fallen off.

Researchers Philip Lucas and Anne Sheeran are proponents of using the head to investigate Bentham's DNA. During his life, writings described Bentham as "eccentric, reclusive, and difficult to get ahold of."

Lucas and Sheeran plan to test Bentham's DNA for autism and Asperger's syndrome. The DNA samples are weak, given the age, and ideal samples should come from bacteria in Bentham's mouth. However, scientists are hopeful they'll be able to better understand Bentham after their studies are complete.

His Body Was Intended To Be A Statement About Social And Religious Practices

Photo: ceridwen / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0Bentham was an atheist and considered the religious practices surrounding the deceased as against utilitarian principles. He rejected the idea of resurrection and the continuation of one's soul; he was critical of organized religion as an "instrument of intimidation, corruption, and delusion."

He also believed society should face the realities of mortality instead of being afraid of or avoiding the topic entirely. Bentham embraced mortality and aimed to find usefulness in it, while alleviating the social pressures around it. According to Bentham, the creation of auto-icons meant "there would no longer be needed monuments of stone or marble - there would be no danger to health from the accumulating of corpses - and the use of churchyards would gradually be done away."

Auto-icons could reside in museums and other common areas, diminishing the fear of mortality "by getting rid of its deformities: it would leave the agreeable associations, and disperse the disagreeable."

He And His Doctor May Have Advocated For The Anatomy Act

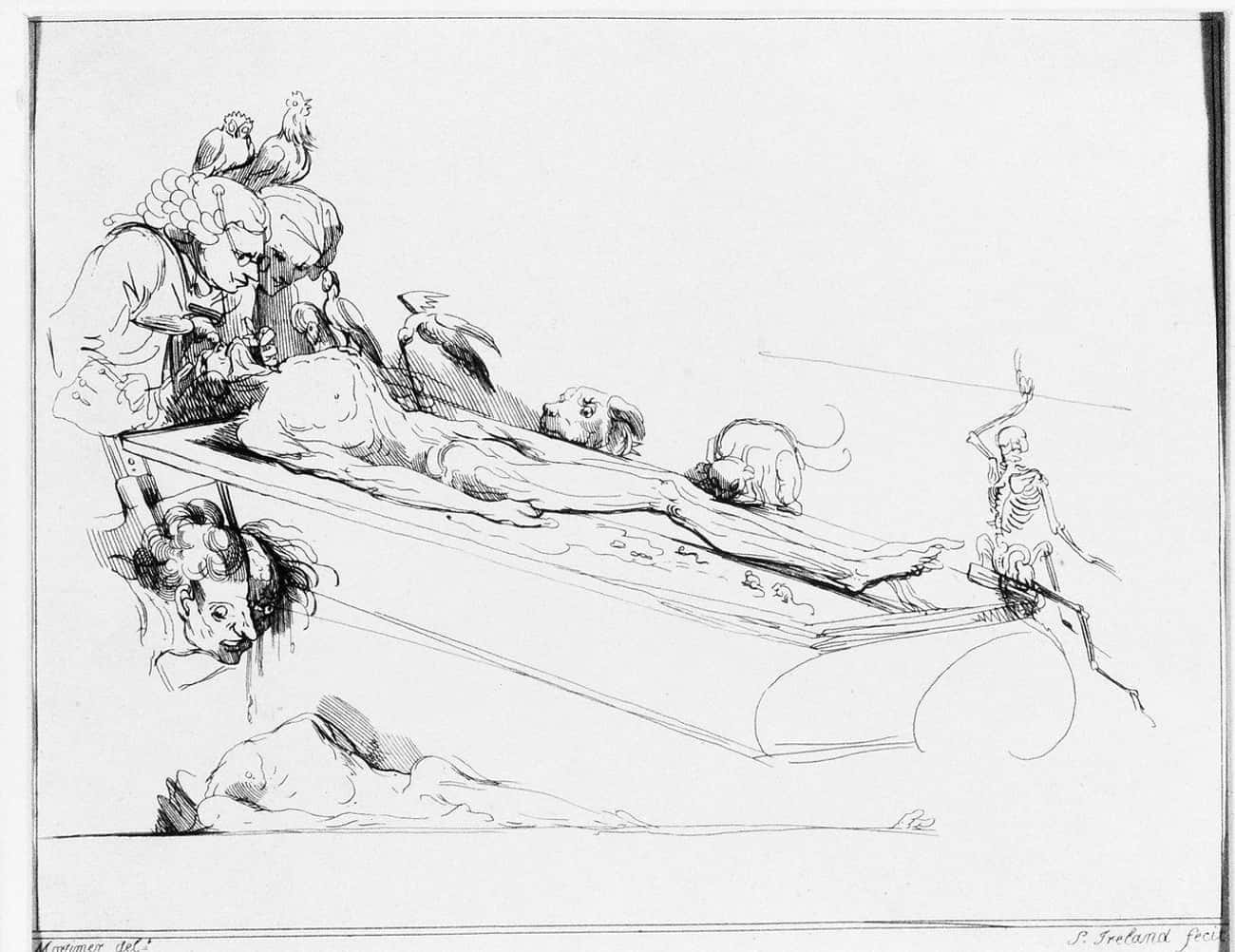

Photo: J.H. Mortimer / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 4.0Both Bentham and Dr. Smith were supporters of the Anatomy Act, a Parliamentary action of 1832 making it easier for doctors to dissect human bodies for medical purposes. Bentham may have helped author the initial versions of the act, which made their way through Parliament during the 1820s. He also supported the mission financially.

The goal of Bentham and others was to make it less taboo for non-criminal offenders to serve as subjects for dissection, which was common in the early 19th century. Bentham's passing in 1832 served as an opportunity for him to match his body to his ideas.

In the months following Bentham's demise, Dr. Smith lobbied hard for the law, which made it legal for unclaimed bodies from workhouses to undergo dissection. The act was less than perfect, and critics claimed it unfairly targeted the poor, but it also helped bring an end to grave robbing and body snatching, both of which were a big problem at the time.

He Finally Got To Visit The United States Almost 200 Years After His Passing

Bentham's auto-icon left London for the first time in 180 years in early 2018, as he made his way across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. Bentham was part of the Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300–Now) exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, which opened in March 2018.

Moving Bentham required exhaustive efforts, while simultaneously revealing more about the body to the public. According to Jayne Dunn, head of collections management at University College London, Bentham "is wearing the original underwear (which has not got infested) and two sets of stockings, one over the other. That might have been the fashion then. Over the top, he has a vest, which is the original.”

While there were no signs of infestation, Bentham's stuffing shifted around with time. Bentham's head (the real one) didn't make the trip.