The general public knows bits about the medieval period. Unfortunately, the general public think they know a lot about the medieval period. Whilst we start learning about this time in our history at school, a lot of what people pick up comes from popular media, in particular films and television series. And, even worse, from fantasy shows “based” on medieval society. The impression most people pick up, then, is that the medieval period was dark, dirty, without colour; people had no hygiene, rotten teeth, never washed and threw their toilet waste into the streets. Food was bland and brown, they had backwards ideas about science, and if you so much as breathed the wrong way the Church would burn you at the stake. Women were constantly attacked and were considered only to be good for childbearing whilst Big Important Men made all the decisions. And everyone was white and Christian.

These myths are so ingrained and so widespread that it is a constant battle for medievalists to fight them. Whilst some liberties in historical fiction are considered acceptable or part of artistic flare (and I have previously written about the Tiffany Effect, where some historical inaccuracies are conversely necessary to make people believe in the programme’s accuracy), a lot of this image of “the Dark Ages” is really damaging to our past. The fantastic Fake History Hunter created a Bingo card a few years ago for frustrated medieval historians to play along and mark off the myths they see. So, I thought now was as good a time as ever to start a series I’ve meant to start for years all about busting some of these medieval myths. And what better to start with than one of the most pervasive: that people believed the world was flat.

Humans have been ‘doing’ astronomy for thousands of years. Even before we invented reading and writing, our ancient ancestors used the stars and celestial bodies to guide their days. They were aware of passing seasons, and that on certain days every year the skies would align in the same position. You can see this at a multitude of ancient monolithic sites where the sun will align down the monument, often during the solstices (one example is the Gavrinis Passage tomb, where the sun shines down the entrance passage and hits the back wall during the Winter Solstice).

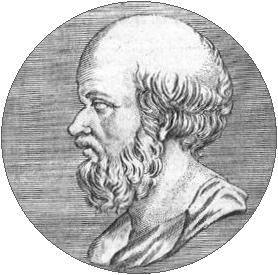

However, exactly what our ancient forebears knew and believed about the sky and its movements largely remains a mystery. But the ancient Greeks is when we have lots of evidence of people really taking time to study the heavens. The earliest concrete evidence we have of ancient people knowing the Earth was round comes from them, back in the 5th century BC – so around 2,500 years ago. The idea spread across scholarly circles in the Greek sphere of influence, and by around 240 BC this led to a Greek polymath named Eratosthenes of Cyrene becoming the first known person to calculate the circumference of the Earth. Although we cannot fully gauge the accuracy of his estimate because he measured it in an ancient unit known as a stadia whose exact length is not agreed upon by historians (ranging from 150-210 metres), his results were incredibly accurate. Accounting for discrepancies in our understanding of the length of a stadia, he estimated the circumference to be within −2.4% to +0.8% of the real value as we know it today with all of our modern technology. Hardly a backwards society.

But that is the Ancient Greeks. Everybody knows they were clever and ahead of their time just like the Romans – but after the fall of the Roman Empire, the Dark Ages arrived and everybody in Europe forgot everything they knew… right? Well, not quite. Although elements of knowledge from the ancient world did fade over time, to be rediscovered independently or through the finding of ancient texts during the Renaissance, the evidence does not point to the suggestion that the knowledge of a spherical Earth did fade. Whilst we cannot account for what the ‘everyday’ person knew or believed, we have countless pieces of evidence that certainly the educated classes of Europe and Asia both believed in a spherical Earth, and continued to be aware of its approximate circumference.

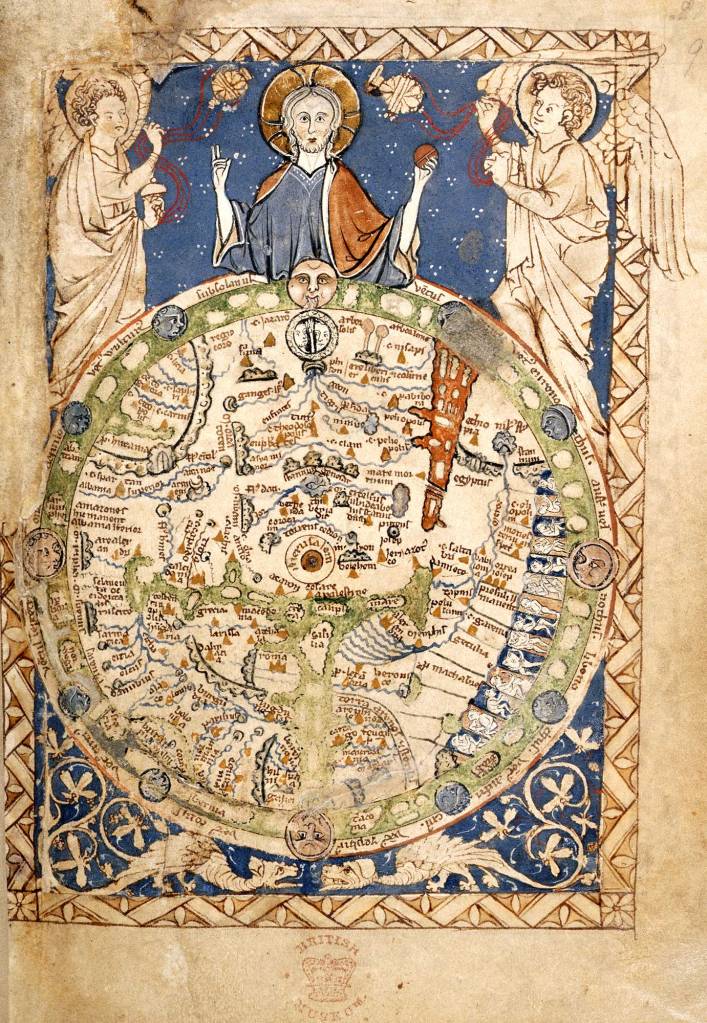

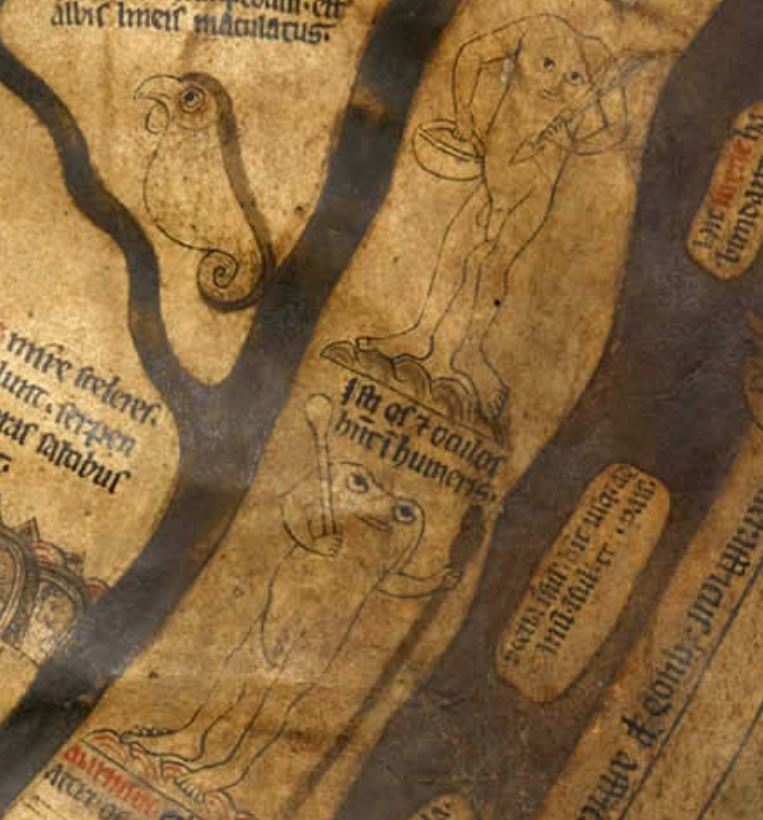

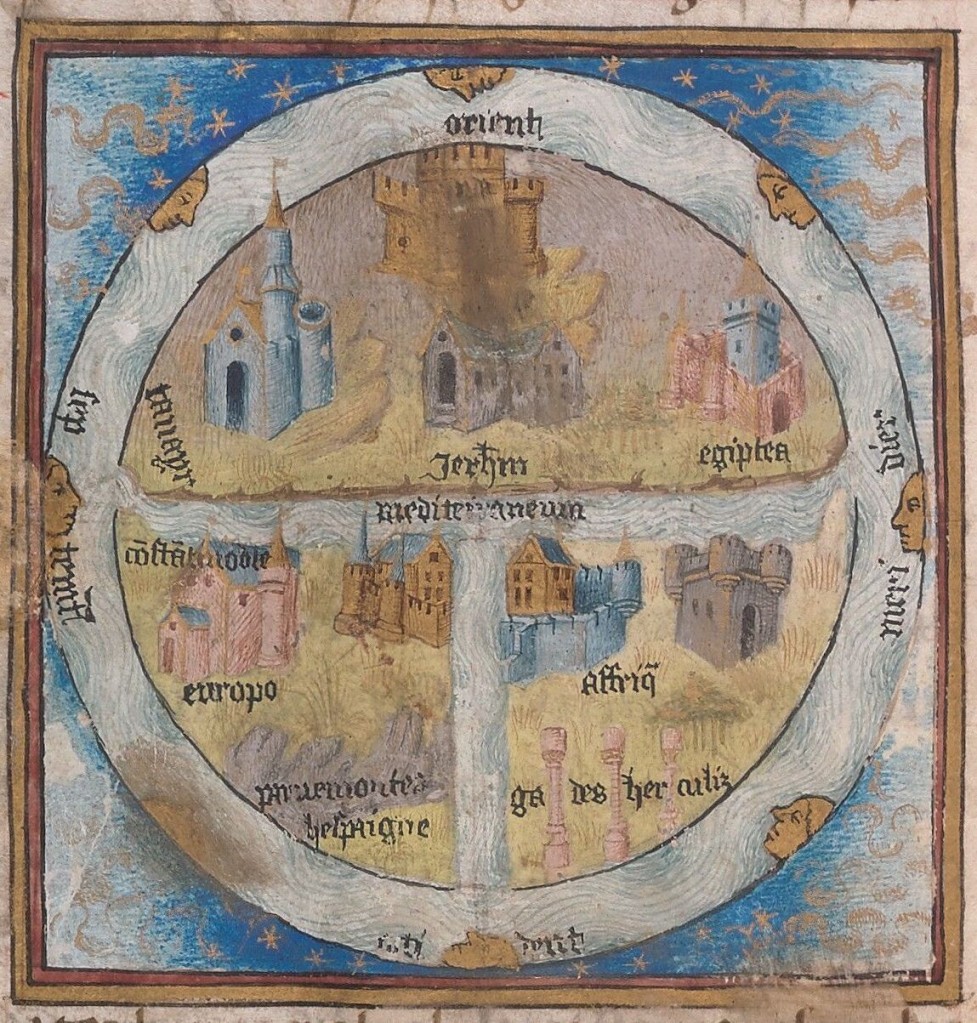

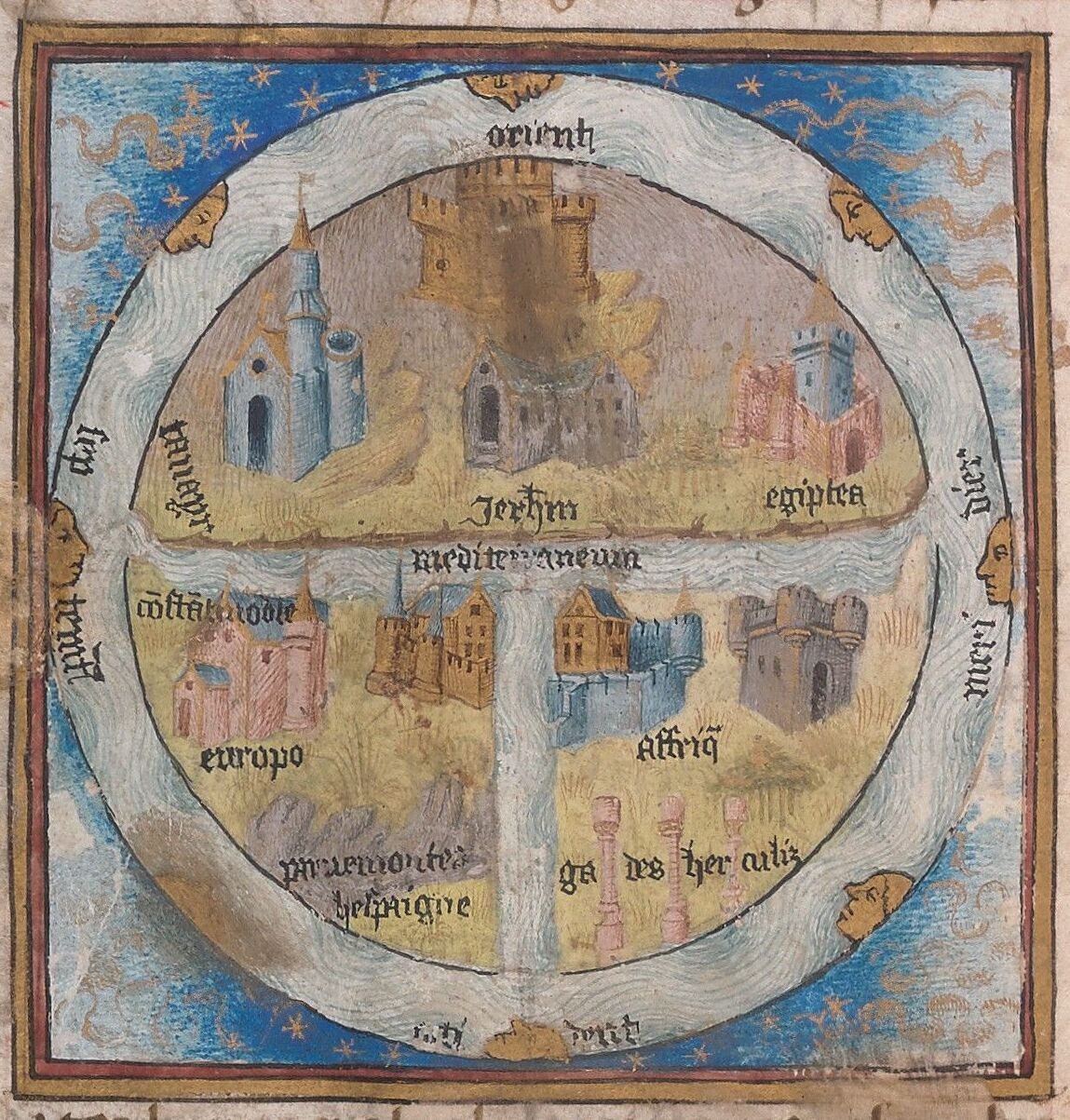

So where did the idea that medieval people believed in a flat earth come from? Part of this error likely comes from depictions of the Earth in medieval art and maps. Some pieces of art did show a flat or disc-shaped Earth, and the 2D nature of maps also lent itself to artistic interpretation. Maps in the medieval period were often not intended to be strict scientific and mathematical instruments in the way we consider them today, and they were often instead intended to portray a concept of the world. Religious sites such as the Garden of Eden often appeared on them, with ghoulish monsters shown on the extremities of the known world. This imagery can encourage us to see the map as the 2D object it is, and thus think that medieval people imagined the world ending at the edges of the map.

The Hereford Mappa Mundi, created c1300, which has mythical creatures around its edge.

We know that the ancient Greeks made globes, but only their celestial ones (marking the stars) survive – none of their globes depicting the Earth. It seems that during the medieval period there was little interest in Europe in creating globes, although some Islamic countries made them. But, the earliest surviving terrestrial globe in the world does come (just about, depending on your definition) from the medieval period. The Erdapfel, or the Nürnberg Terrestrial Globe, was made by a German man called Martin Behaim some time between 1490 and 1492.

Behaim’s globe is fascinating for the period it was made, for it was completed just before the return of Columbus’ voyage and so the Americas are not shown on the globe because knowledge of their existence had not yet reached Europe. Behaim made the globe for the Imperial City of Nuremberg, at the time an independent city within the Holy Roman Empire.

But the point about the exclusion of the Americas brings us to another piece of evidence that people by this time believed the world was round; for that was the basis for Columbus’ journey. The reason the West Indies are called that is because, knowing the world was round, Columbus was attempting to sail the ocean westward bound in order to reach China and India. For centuries, the Silk Road had been used as an overland trading connection between Europe and parts of Asia, but by the mid-15th century the Ottoman Empire had taken control of Constantinople, a key point on the route. Christian Europe needed another way to reach the East, and one way was by sea. The biggest opposition Columbus faced to gaining funding for his voyage was his contemporaries at court arguing that the journey was (rightly) far too long to make with enough provisions.

So if we have so much evidence that people throughout the medieval people knew the Earth was round, why do we think contrary today? In the 17th and 18th centuries, several pieces of literature seem to have used people believing the Earth was flat as a comedic device or a way to discredit one’s opponents by pointing out how unintelligent they were. This, though, was still very much bringing the audience in to “knowing” the joke and was not necessarily targeted specifically at medieval people. Instead, as with many other things, we can trace the myth back to the 19th century.

One of the most important pieces of literature which spread the idea amongst the general public that medieval people thought the world was flat was published in 1828 by Washington Irving. He wrote a biography on Christopher Columbus (the guy we just discussed knew very well the world was round, along with all of his opponents) where he created a scene wherein Columbus’ opponents used the Bible to contradict his idea that the world was round.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

Irving’s idea that the strong Christian religion of medieval Europe was a barrier to scientific ideas was picked up by several scientists within years of publishing. Any example they could find of early figures disputing a round Earth were used as evidence (and there were very few), whilst ignoring the fact that these few writers were mocked at the time and later in the medieval period for trying to claim a flat Earth. But the hook had developed, and writer after writer picked up the myth and rolled with it.

Though in the 20th century, writers and historians fought back against the myth and tried to explain that medieval people never really believed in a flat Earth, the image had captured the public imagination. It continued to be portrayed in popular media and even in school books which were much more readily available to the public than academic texts, and thus the myth took hold. Even today, many people continue to think that it was true, drawn both by the idea that people in the past must not have been as clever as us, and, for many, finding appeal in the idea of an evil, backwards religion that was intent to destroy progress and dissenters to their ideas.

Part of what spurred these myths may have been that in the Early Modern period, from the early 17th century, the Catholic Church did have problems with people like Galileo claiming that the Sun was the centre of the universe rather than the Earth. This, they claimed, did go against the teachings of the Bible, and they strongly fought against the idea. However, this was during a time of huge religious change, after decades of dissent from the Church through the creation of Protestantism and other Christian denominations. The Church was desperate to keep control over their authority and teachings and were much less open to new ideas. And, it was most definitely not at all the medieval period.

So, for over 2,000 years most people in Europe and beyond have known that the world is indeed round. The country was not filled with ignorant peasants and an overbearing Church and State who would quash any suggestion that the world was not flat, and for much of that time our ancestors even knew with a fair degree of accuracy the circumference of our planet. Maybe we can finally lay this myth to rest.

Did you know that Just History Posts now has a newsletter? Be sure to sign up here!

Previous Blog Post: Historical Figures: Edward Montagu, Knightly Criminal

You may like: Historical Objects: The Hereford Mappa Mundi

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Read more:

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2018/05/the-earth-is-in-fact-round.html

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44251730

https://www.medievalists.net/2023/05/the-myth-of-the-flat-earth/

As a history teacher, I have to fight every year with this myth. It’s really rooted deep into people’s minds. Thanks for the great article, I will use it in class.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can imagine! It’s funny what a strong hold it has taken in people. Thank you so much!

LikeLike

I am in the midst of editing a medieval-inspired fantasy, and your post has given me lots of really useful examples to think about! I shall take extra care not to include the Bingo myths; my fantasy world will have lots of colour and joie de vivre 😅

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha that makes me so happy to hear!! Good luck with the editing 😄

LikeLiked by 1 person