What It Was Like To Be An Inmate At Alcatraz

- Photo: Jet Lowe / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

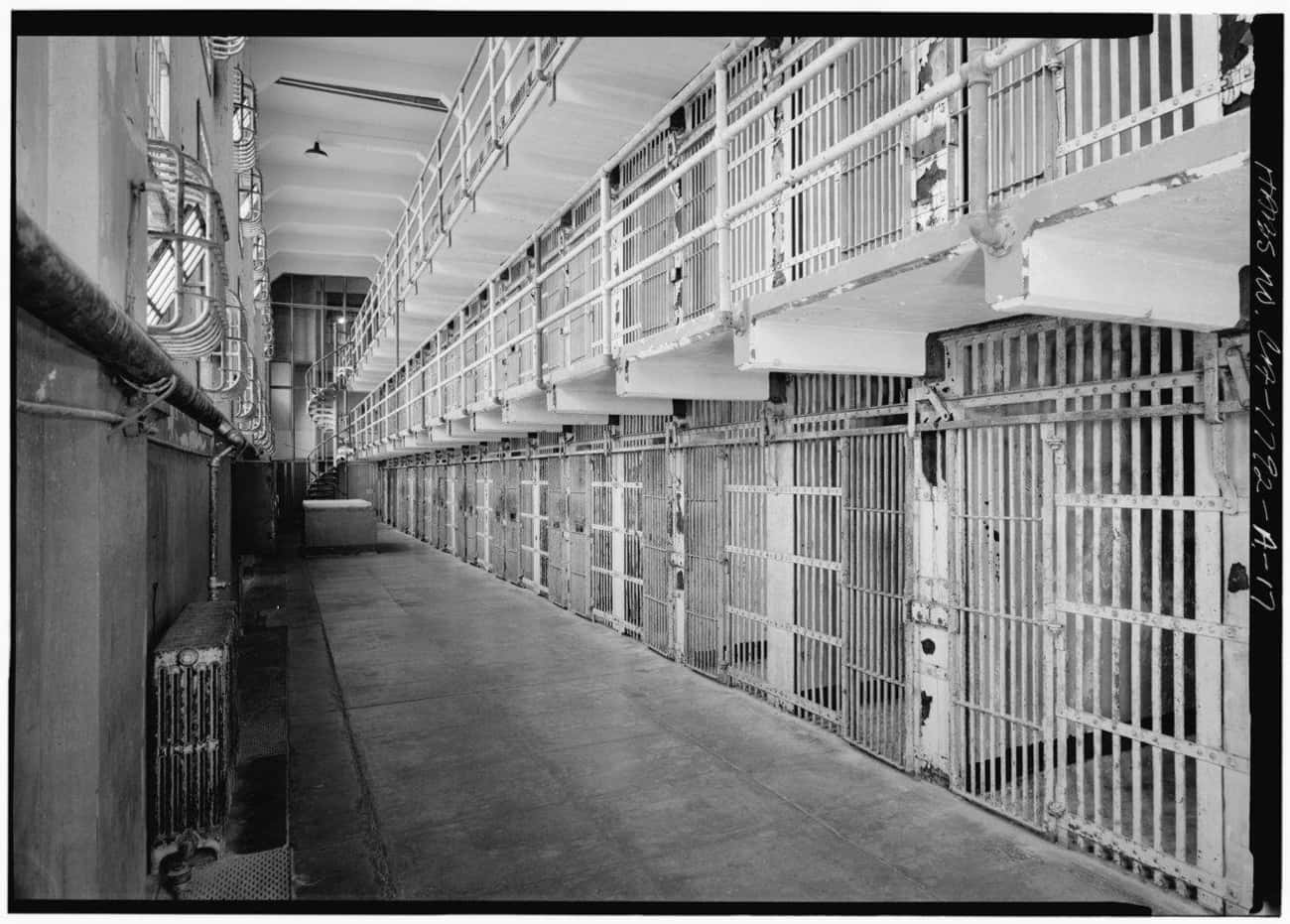

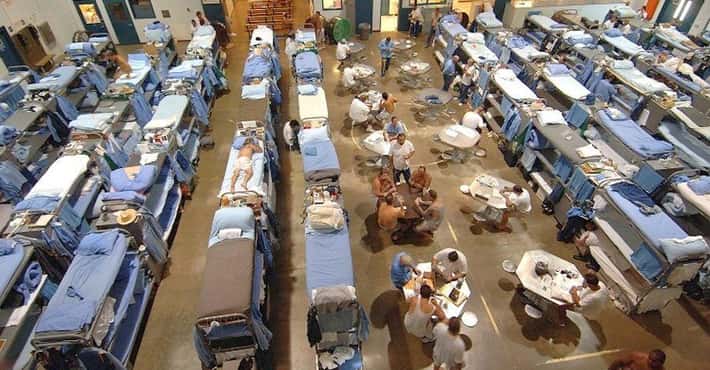

There Was A One-Inmate-Per-Cell Rule

Inmates at Alcatraz, which had a capacity of roughly 330 men, had individual cells. This allowed for safety and privacy - inasmuch as one could have them in prison - and some federal prisoners actually requested incarceration at Alcatraz as a result. William "Willie" Radkay, who occupied a cell next to friend and colleague George "Machine Gun" Kelly at Alcatraz, saw having single cells as an advantage, one that prevented unwanted advances.

Cells were divided into blocks, with blocks B and C housing 336 cells that measured 5 feet by 9 feet. Cell block D was reserved for inmates in solitary confinement; while those cells were a bit bigger, prisoners spent 24 hours a day there. The only times cell block D inmates left their cells were for weekly visits to the recreation yard. Cell block A, the most broken-down part of the facility, was never used to house inmates for any significant length of time.

Landing in solitary confinement resulted from breaking rules and could last anywhere from a few days to multiple weeks. According to former inmate Jim Quillen, "A day in the hole was like an eternity."

- Photo: jimmywee / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0

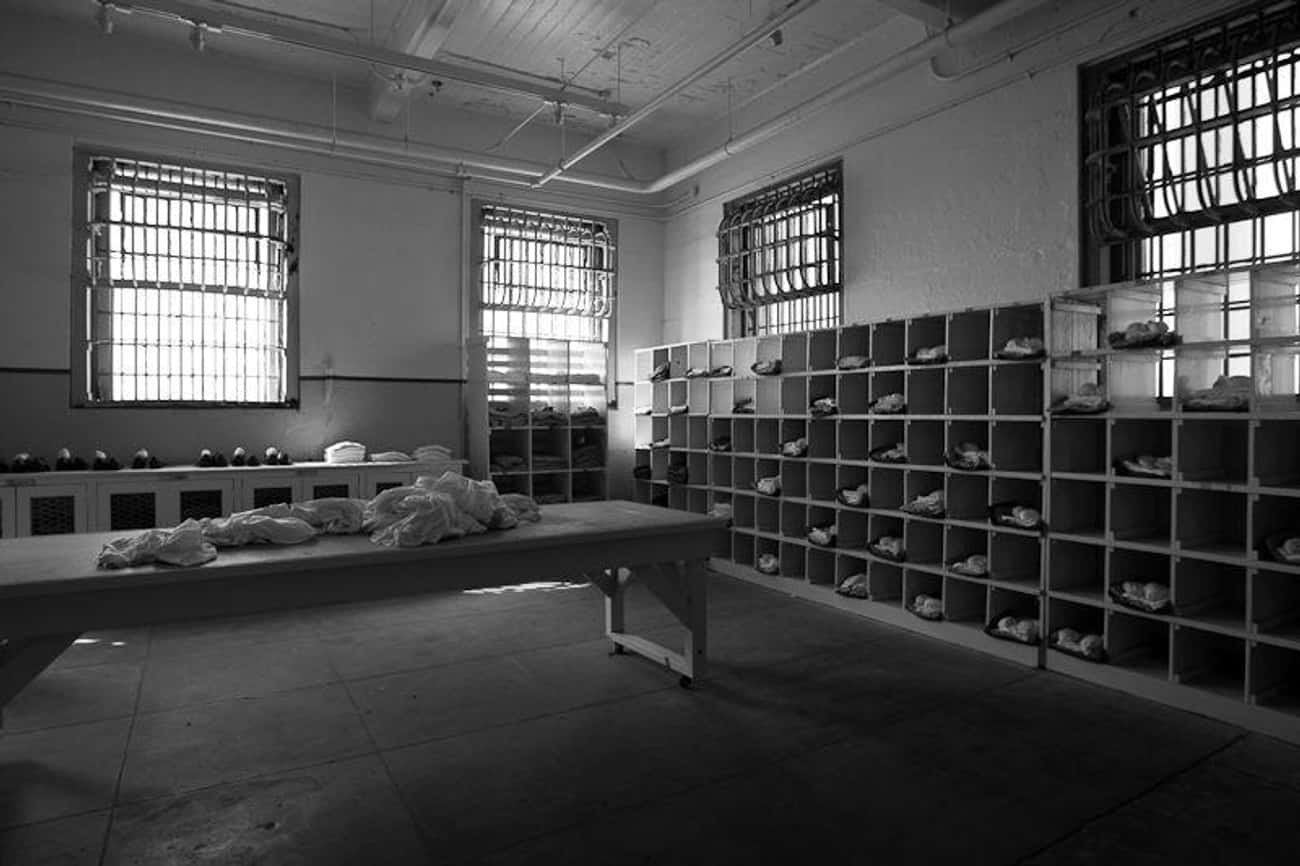

Prisoners Had 'Four Rights' - Food, Clothing, Shelter, And Medical Care

Rights and privileges at Alcatraz were very different things. All prisoners had four rights: clothing, food, shelter, and medical care. Anything beyond that had to be earned.

When a prisoner arrived at Alcatraz, he was sent to the clothing room. Once there, he was stripped of what he was wearing and sent to the showers, then received a standard-issue, stamped uniform. While in the clothing room, prisoners also underwent a cursory medical exam and were strip searched.

Prisoners got three meals a day, a roof over their heads, and visited the hospital when needed. Al Capone, for example, spent time in the hospital for symptoms related to syphilis. In addition to first aid and other medical care, the hospital at Alcatraz provided dental and psychiatric services. Until the 1950s, there was a physician-in-residence at Alcatraz, but budget cuts led to the use of contracted doctors during the final years the prison was open.

The hospital at Alcatraz also served as a permanent home to some prisoners. The Birdman of Alcatraz, Robert Stroud, spent 11 of his 17 years at Alcatraz in the hospital. This was, in part, because he had a kidney condition, but he was also dangerous and needed to be kept away from other prisoners.

Prisoners Could Earn Access To The Library And Other Activities

The library at Alcatraz was located in D-Block and housed roughly 10,000 books. Access to the library was something prisoners earned and, as a result, the privilege could be taken away at any time.

Getting a book didn't involve visiting the library, however. Each morning, prisoners with library privileges filled out a card requesting items. According to former inmate Floyd Harrell, "Every prisoner had a catalog listing of books that were supposed to be in the library." Books, magazines, and the like were delivered to the prisoner's cell. All crime-related content was removed ahead of time.

Because reading was one of the few escapes afforded to prisoners, some took full advantage of what the library had to offer. Robert Stroud studied law and reportedly learned several languages, while other inmates took correspondence classes offered through the University of California, Berkeley.

In addition to the library, prisoners also earned access to recreational activities like chess or softball, visits with family members, and work duty. During the 1950s, prisoners could listen to the radio via headsets and watch movies in the prison auditorium.

Just like the library, any of these privileges could be taken away if an inmate didn't follow the rules.

- Photo: Arnold W. Peters / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

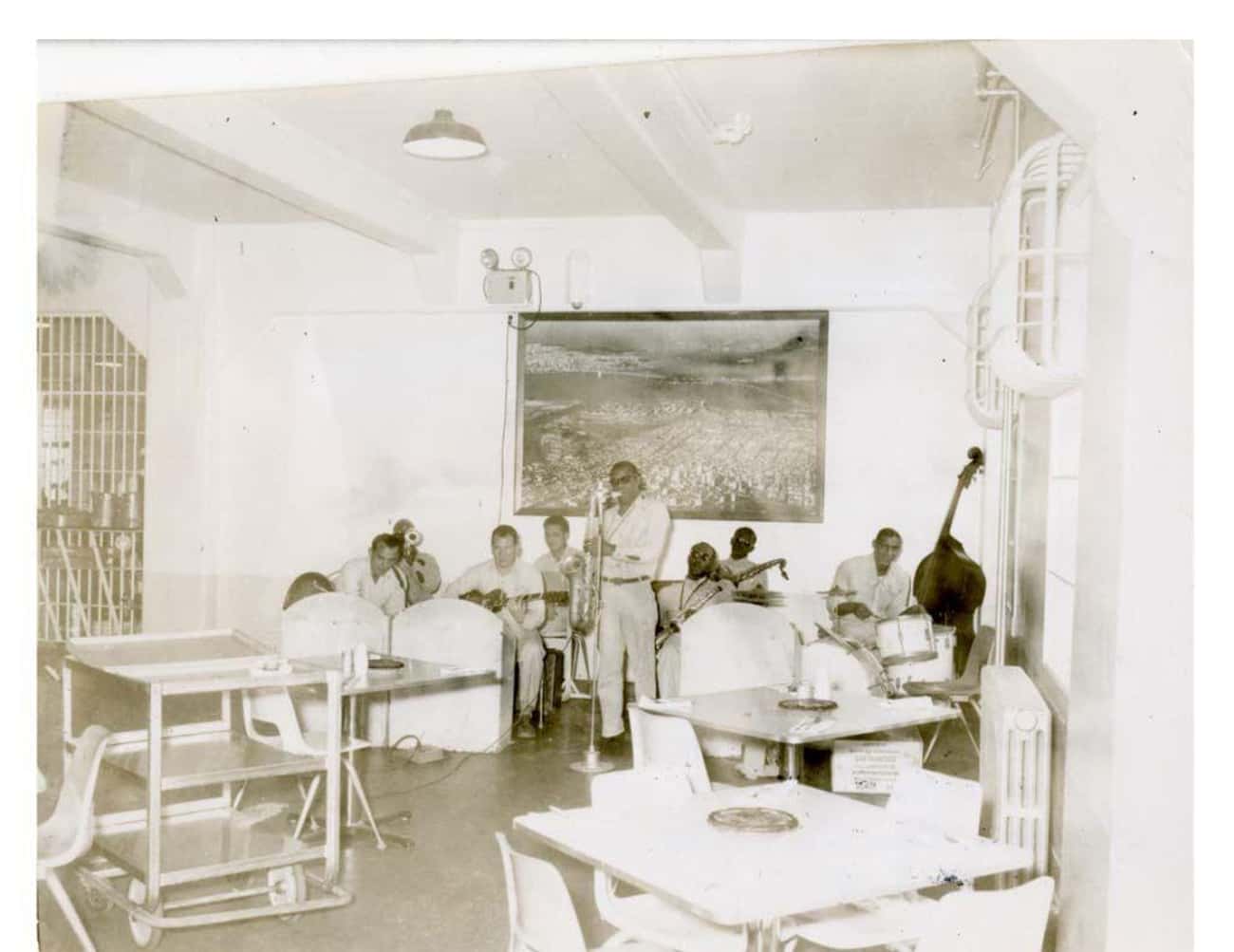

Prisoners Had The Opportunity To Play In The Inmate Band

The Alcatraz band, called the Rock Islanders, was made up of inmates who had earned the privilege to play. There were numerous Rock Islanders over time - including Al Capone, who begged to join and eventually earned a spot. According to a letter Capone wrote to his son while serving time at Alcatraz, he "learned a Tenor Guitar and then a Tenor Banjo, and now the Mandola," and could play more than 500 songs.

The band itself was, in the words of former guard George Gregory, "only a cut above a fourth- or fifth-grade band, but it did wonders for their self-esteem." The band played on holidays in the dining hall with Sunday and special-event performances as well.

Prisoners could buy musical instruments but, in accordance with the regulations issued in 1956, could only practice "between the hours of 5:30 pm and 7 pm. No singing or whistling accompaniments will be tolerated. Any instrument which is played in an unauthorized place, manner, or time will be confiscated and the inmate placed on a disciplinary report." Guitar strings were regulated and "an old set of strings" had to "be turned in to the cellhouse officer to draw a new set."

- Photo: William Warby / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0

Cells Were 5x9 And Came With A Cot, Wash Basin, And Toilet

The extremely small cells at Alcatraz featured a cot, a sink, and a toilet - with very little else.

When Jim Quillen arrived at Alcatraz in 1942, he recalled getting to his cell where he saw, "a steel bed, a straw mattress, and a dirty, lumpy pillow." He also "noticed the cell contained a toilet with no seat... [and] at the end of the bed, next to the toilet, was a small washbasin with only one tap. Cold water!"

In additional to a shelf above the sink and a small table that could be folded down from the wall, Quillen and his fellow inmates had no creature comforts. Over time, inmates might accumulate personal items. Alcatraz didn't have a commissary and prisoners couldn't have items sent from the outside, but prison regulations during the 1950s allowed prisoners to "purchase certain items such as textbooks, correspondence courses, musical instruments, or magazine subscriptions."

George Gregory, a guard at Alcatraz for a time, remembered unsuccessfully trying to get an inmate, Conlin, to clean up his cluttered cell. In the end, Gregory took a box into Conlin's cell and removed "mostly junk," including "a pillowcase stuffed with socks" and "a pair of ladies' panties" the prisoner had stolen from the laundry. The underwear, apparently, belonged to the warden's wife.

There Was A Rule Of Silence Until The Late 1930s

The first warden at Alcatraz, James A. Johnston, instituted a code of silence at the prison. Prisoners were only allowed to speak at meals or during recreation time. Johnston also allocated each prisoner three packs of cigarettes each week, prompting at least one observer to note that smoking was more common than talking.

To get around the rule, inmates resorted to using the pipes between cells to communicate. The rule only lasted until 1937 because it was generally considered cruel and too difficult to enforce.

Silence remained the norm in solitary confinement, however. Jim Quillen described "total silence and darkness" as his "constant companions for twenty-four hours of each" of the 19 days he spent in "the hole."

- Photo: Carl Sundstrom / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

The Food Was Better Than You'd Expect

As food was one of the rights afforded to prisoners at Alcatraz, inmates ate three meals a day. They were served breakfast at 6:45 am, with lunch at 11:40 am and dinner at 4:25 pm.

The food at Alcatraz was generally regarded as being some of the best served within the federal prison system. Some who worked in the kitchen had backgrounds in cooking and took pride in what they presented to their fellow convicts. Former inmate Bryan Conway recalled in 1938, "Food at Alcatraz is much better than usual prison fare. For dinner, there is meat, beans, coffee, bread, celery; for supper, chili, tomatoes, and apples, with hot tea."

According to a menu from 1946, inmates ate stewed fruit, cereal, milk, bread, and coffee for breakfast. Lunch, the biggest meal of the day, included soup and meat - everything from roasted pork shoulder to beef pot pie - with vegetables, bread, and tea. Some additional lunch items could include apple pie, cole slaw, and corn on the cob. There was mustard, ketchup, and gravy at the ready as well.

Dinner was similar in presentation, with some lunch items reappearing at the evening meal. Prisoners ate soup, vegetables, and bread with fruit, cake, or Jell-O as dessert. Bread and coffee were staples at dinner, too.

- Photo: Arnold W. Peters / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

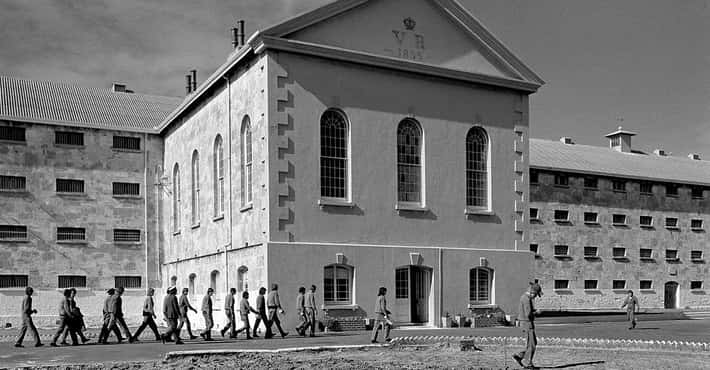

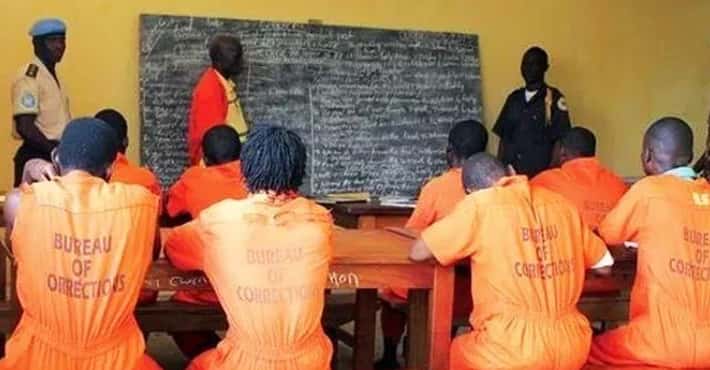

Each Prisoner Worked For Most Of The Day

Work at Alcatraz was a welcome way to pass the time. Prisoners not in solitary confinement could work a variety of jobs in the laundry, kitchen, burning trash, tending the docks, or similar tasks. Inmates marched to their jobs after breakfast each morning, in the process earning in the range of 5-12 cents an hour.

Industry jobs like the laundry and woodworking plant allowed prisoners to deduct two days from their sentences for each month worked during the first year. During the second through fourth years, it was four days; the fifth year and all subsequent years earned inmates five days per month.

Prisoners reported to their respective workplaces at 7:20 am and were actively working within 10 minutes. They had one rest period during the morning but worked until lunch, after which they went back to work. A brief break during the afternoon was the only reprieve until dinner. Once prisoners ate their evening meal, they returned to their cells until the next morning.

Inmates didn't work on the weekends or holidays. Those with privileges took part in recreation time, often outside. One former inmate, Bill Baker, remembered planting a tree at Alcatraz in the recreation yard. One of the guards watched him nurture the tree and "came over and said 'What are you watering... these weeds for? They don't need watering.'" Baker replied, "Oh, just something to do, you know." His tree was gone the next day.

- Photo: Carl Sundstrom / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

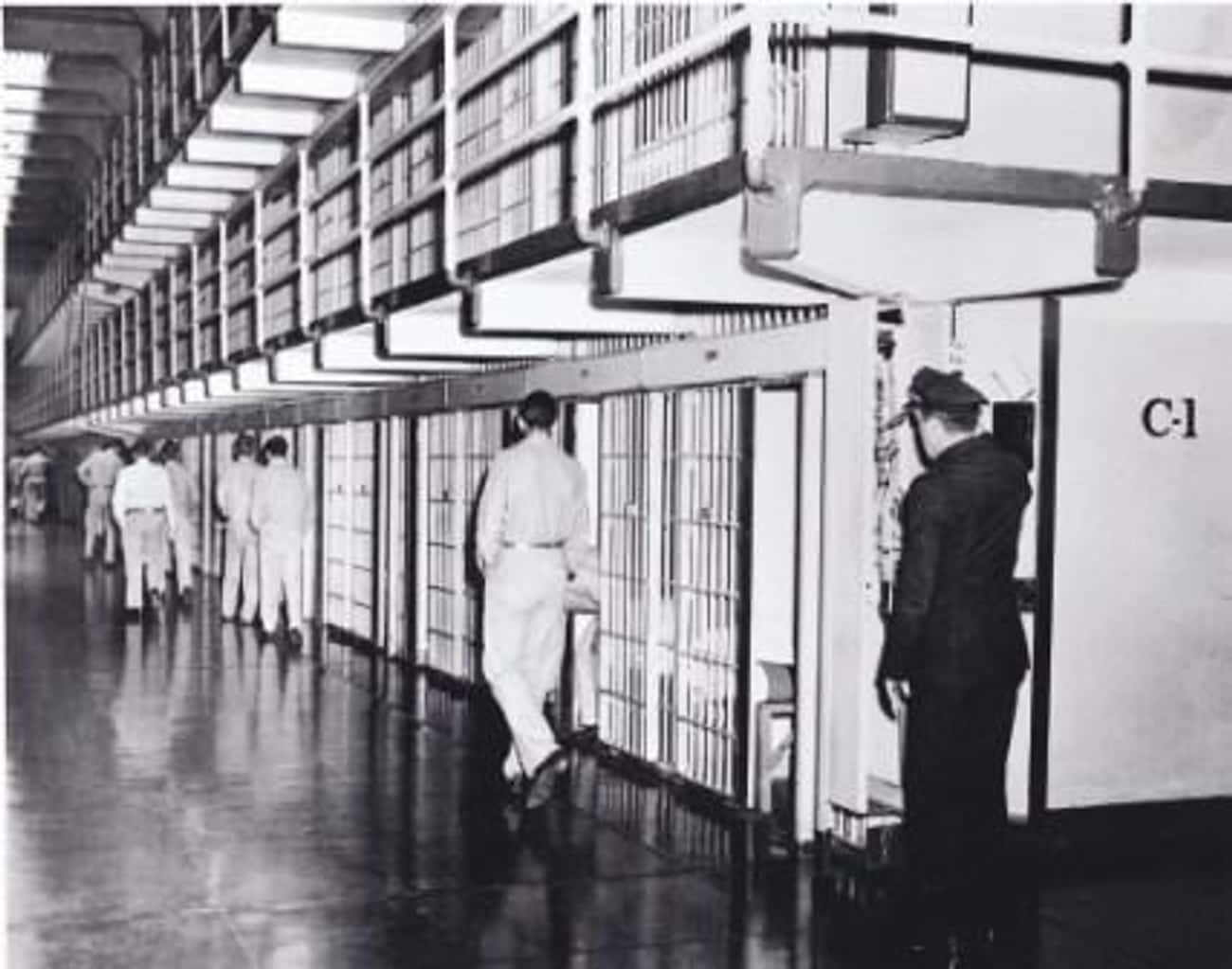

Prisoners Were Counted Several Times A Day

In an account of his time at Alcatraz, prisoner Bryan Conway noted that a "bell was the signal for the count of prisoners - a really serious business which is done every 30 minutes." Later records indicate counts didn't take place quite so often, but that there were 13 counts each day.

Prisoners were counted first thing in the morning, lining up outside their cells before marching to the mess hall for breakfast. After eating, they again lined up to go to work, where they were counted again. After their morning break, prisoners were subjected to a count, an activity that was repeated before they marched to lunch as well.

After lunch, inmates briefly returned to their cells for a formal noon headcount before work, where they were counted again. Another count after their mid-afternoon break preceded the count inmates underwent before dinner. After they ate, prisoners went back to their cells for the night, but not before being counted one more time.

While prisoners spent their evenings reading or doing whatever they could to pass the time until lights-out at 9:30 pm, they were counted two more times. Overnight, as prisoners slept, guards made rounds and took an additional two headcounts.

Foremen also took an additional six counts throughout the day. Saturday, Sundays, and holidays ran on different schedules, but prisoners' total number counts were comparable.

Guards Used A Rudimentary Metal Detector To Check Prisoners For Contraband

When Bryan Conway got to Alcatraz in 1938, he was introducted to the "snitch box," a metal detector used to search prisoners. Conway remembered:

One day the snitch box sounded an alarm on every man who came from the laundry. The guards jerked each man out of line, searched him, and found nothing. It took hours to locate the trouble, which was merely that the machine was so finely adjusted it was detecting the metal eyelets in the men's shoes. A few days later it was silent when two men passed through with knives in their pockets. But the guards don't trust the "electric eye"; they search every 12th man, whether the alarm has sounded or not.

The "snitch box" - built by the Teletouch Corporation - was one of three metal detectors placed at Alcatraz. Prisoners and visitors had to pass through them, which at one point caused Al Capone's mother great embarrassment. When she set it off with her corset during a visit, Teresina Capone had to "strip down to her corset, revealing the metal stays that had tripped the metal detector."

- Photo: Laika ac / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0

There Were Limitations To How Much Prisoners Could Communicate With The Outside World

Because so much of life at Alcatraz was an earned privilege and not a right, keeping in contact with anyone on the outside was subject to the judgment of prison authorities. Prisoners in solitary confinement were denied all correspondence and outside contact. Other prisoners could send and receive letters, although the amount of contact they had was regulated and monitored.

Bryan Conway was "permitted to write only one letter of not more than two pages each week." Such correspondences "had to be to a blood relative; no inmate could write to his sweetheart."

On Mother's Day, prisoners could send an additional note to their mothers, but all correspondence had to be approved by prison officials. Incoming letters were never sent directly to prisoners; instead they received copies or typed versions of handwritten notes.

Just like everything else, visitation was also heavily regulated. Once prisoners earned visitation time, their prospective visitor had to request permission. Prisoners got one visitor each month for 90 minutes, but it had to be a blood relative or wife. The two parties talked to each other on phones while looking at each other through glass, but the conversations were monitored. If either person began to talk about prison or other inmates, the visit came to an end.

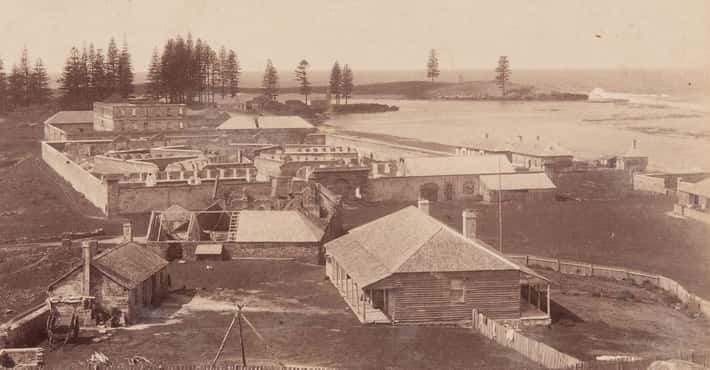

Escape Attempts Happened Every Few Years

There were 14 attempted escapes from Alcatraz, collectively involving 36 prisoners. A total of 1,545 men served time at Alcatraz, so the attempt total isn't too outrageous; the efforts of the would-be escapees, however, certainly could be. The first attempt, in 1936, involved Joe Bowers attempting to climb over a fence. He was shot, fell from his vantage point, and perished because of his injuries. The next year, Theodore Cole and Ralph Roe escaped and tried to swim to San Francisco, only to get caught in a storm and, most likely, get lost at sea. Their remains were never found.

Failed escapes in 1938, 1939, and 1941 were followed by two unsuccessful attempts in 1943. In 1945, John Giles used his prison job in the loading dock to slowly piece together an army uniform from laundry sent in for cleaning. He donned the uniform on July 31, 1945, and made it all the way to Angel Island, where he was apprehended and sent back to Alcatraz.

The following year, during the "Battle of Alcatraz," a half-dozen prisoners overpowered guards and seized weapons, only to discover they didn't have the key to open the recreation yard and exit the facility. As a result, they incited a riot and exchanged gunfire with several guards. After two days, the battle was over, but three prisoners and a pair of guards did not survive.

Floyd Wilson tried, unsuccessfully, to escape a decade later; In 1958, two men tried to swim from Alcatraz to the California coast. On prisoner, Clyde Johnson, was apprehended, but the body of the other, Aaron Burgett, washed ashore two weeks later.

In 1962, Frank Morris and the Anglin Brothers, John and Clarence, disappeared from their cells, never to be heard from again. In the 1979 movie Escape from Alcatraz inspired by true events, it's believed that, after they slipped through enlarged vent holes in their cells and shimmied down a drainpipe, they tried to swim to freedom but most likely drowned in the process. The same year, two men escaped from the kitchen and, again, tried to swim to San Francisco. Both prisoners were discovered and returned to Alcatraz.

- Photo: Barnellbe / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

Many Prisoners Went Mad From Isolation And Mental Torment

According to inmate Brian Conway, the monotony and strict discipline at Alcatraz drove 14 of 317 prisoners "violently insane" during his "last year on the Rock." He recalled that many more were going "stir crazy." To compound the isolation and restlessness, Conway indicated guards would practice shooting at night, something that deprived prisoners of sleep and caused a great deal of anxiety. Conway described one particularly horrific instance of madness among inmates:

A convict working on the dock detail suddenly picked up an ax, laid his left hand on the block, and chopped off every finger. Then he laid his right hand on the block and begged the guard to cut it off, laughing like a demon all the while.

At times, doctors thought prisoners were faking their mental struggles. After prisoner Joe Bowers got to the prison in 1934, he refused to work and was put into solitary confinement. He attacked guards twice, "striking them blindly with his fists," and was diagnosed as epileptic. A few months later, a psychiatrist assessed him, admitting there was cause to believe Bowers was "truly psychotic," but cautioned that he had "something to gain if he can induce us to believe that he is insane." After it was agreed that Bowers was faking, he was sent back to his cell, where he tried to take his own life several times. Bowers passed in 1936 while trying to escape from Alcatraz.

In 1935, former inmate Verrill Rapp told reporters that prisoners were going insane because of the treatment at Alcatraz. When Henri Young was tried for slaying a fellow inmate at Alcatraz in 1941, his lawyers used the harsh treatment at the prison as part of his defense.

All told, there were five men who took their lives at Alcatraz and eight slayings committed by inmates during the 29 years the prison functioned.