This 1800s Scientist Tried To Create Real-Life Frankensteins By Electrocuting Corpse Brains

Electricity Could Have Been The Essence Of Life, Which Motivated Scientists To Use It On Corpses

Electricity was once thought to be the "essence of life." Scientists of centuries past were searching for the "spark" of life, at first metaphorically and later literally. Some scientists believed that electricity contained the origins of life – that electricity itself was a biological fluid that could be activated – and it could help scientists better understand diseases. This search for life led to many experiments involving electricity, especially as religion began to lose its hold, and it became more acceptable to look at the world through a scientific lens. No longer thought to be God's wrath toward humanity, electricity became ground zero in the search for the elixir of life.

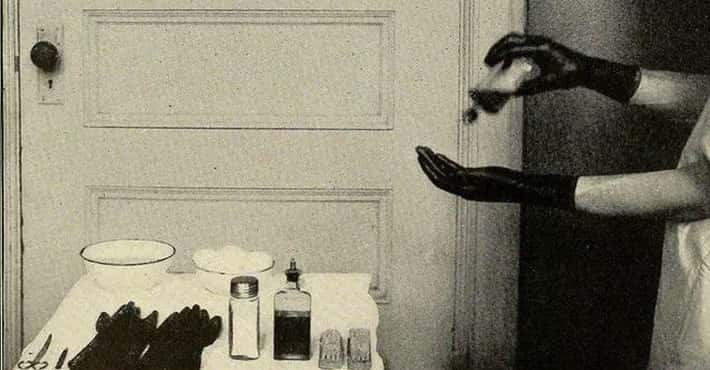

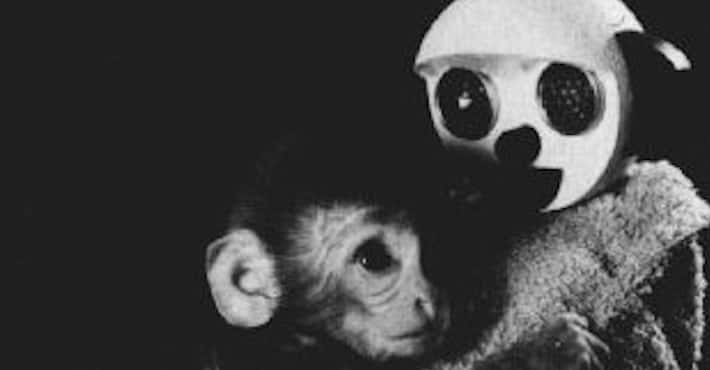

At First, Scientists Practiced Galvanism On Animals, Including Frogs And Kittens

The process of using electrical currents to make biological material appear to move is called galvanism, named after the man who first demonstrated the practice, Luigi Galvani. Many scientists practiced their experiments with electricity on animals instead of humans. For his part, Galvani used the bodies of frogs for his theories, and Karl August Weinfold used kittens. The latter decapitated healthy kittens and make the bodies twitch and move using electric currents. Other scientists used much larger animals, like the decapitated heads of cattle.

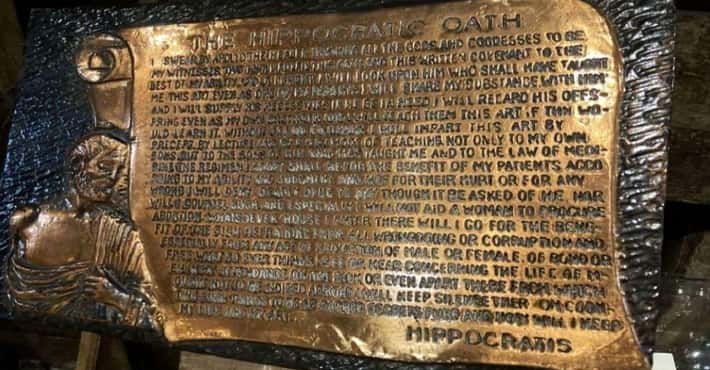

The "Murder Act" Provided Human Specimens To Scientists

In 1751, England passed the Murder Act. This law meant that all people who were executed after being found guilty of murder could have their bodies used for scientific purposes, and the law had multiple benefits. First, the anatomists of the time were desperately in need of bodies, and they would have more corpses to study with the bodies of criminals readily at their fingertips. And second, it was seen as an additional punishment for the criminals, since having your body dissected was seen as desecration, harming your chances of success in the afterlife.

Matthew Clydesdale, Ure's Intended Frankenstein, Was A Murderer

In August of 1818, 35-year-old Matthew Clydesdale drunkenly murdered one of his fellow coal miners, an 80-year-old man. The murder weapon was a coal pick. It was for this crime that Clydesdale was sentenced to death by hanging. After being hung and having his body drained of its blood, Clydesdale was put on the experimental table, an attempt at his resurrection about to begin.

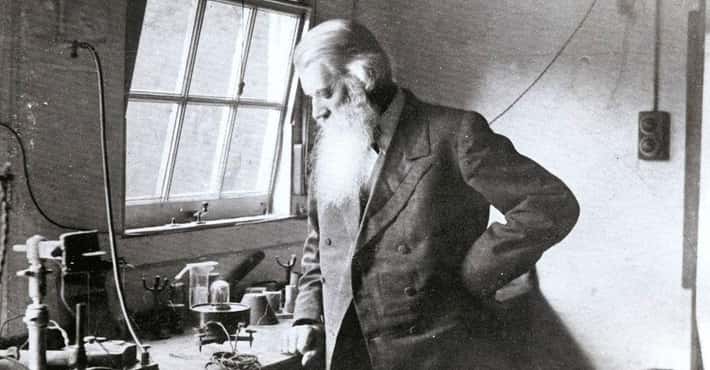

Andrew Ure Had No Experience With Electricity, But You Can't Keep A Good Scientist Down

Ure was a well-educated man, who was a professor of chemistry at Anderson College, and he had quite the (good) reputation as a practical chemist. However, he had no known practical experience with electricity. He was interested in a seemingly wide range of topics, and for the experiment, he was acting as an assistant to anatomy professor James Jeffray. Ure was considered a relatively minor figure in scientific history, and his experiment on Clydesdale is one of his most well-known endeavors.

The Experiment Produced An Hour Of Ghastly Contortions, Which Made Some In The Audience Faint

Ure carried out his experiment by touching an electrical current to incisions made at Clydesdale's fingertips, hips, neck, and heels. Ure noted how he could make the diaphragm rise and fall as if the body was breathing, and he also made the fingers unclench and point to different people around the room. This had the effect of completely freaking out many of his observers, one of whom actually fainted.

Ure later described the look on Matthew Clydesdale's face as he shot electricity through his body: "Every muscle in his countenance was simultaneously thrown into fearful action; rage, horror, despair, anguish, and ghastly smiles, united their hideous expression in the murderer's face..."

Success Would Have Been Seen As A Bad Thing

Andrew Ure's main goal was to bring life back to a dead body; however, this subject was probably not the best choice for completing that goal. Had he successfully brought Matthew Clydesdale back to life, he would have been bringing a murderer back into the population. There wasn't much he could do about that situation, considering that "good citizens" at that time did not donate their bodies to science or consent to being experimented on.

And it seems that Ure didn't lose much sleep about his failure, either – at least when it came to critiquing his method. He reasoned that using electricity as a resurrection technique was bound to fail since Clydesdale had died as a result of violent injury.

Even Though He Failed, Ure Profited Off The Event

Despite failing – and collecting no usable or helpful data from his experiment – Ure capitalized on the strangeness of what he had tried to achieve. He published his results in a pamphlet (that he wrote and sold). His medical contemporary described Ure's acts as "publicity of the crudest kind... This rather ‘Gothick’ experiment, reported in such appropriate literary style, no doubt made Ure’s name better known."

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein Was Published The Same Year, Capturing The Scientific Fervor Of The Era

Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein was published in 1818, the same year that Ure carried out his experiment. The timing of Ure's real-life Frankenstein seems to be a coincidence, since many scientists at the time were experimenting with galvanizing as a method. The book may add some dramatic literary flourishes, but it fits very well with what was happening in the scientific community at the time.

Though Ure's experiment coincided with the publication of Shelley's novel, the latter had been working for two years prior to the actual publishing.

Electrical Experiments On Human Corpses Soon Went Out Of Fashion

Although fascinated by these galvanizing experiments at the beginning, the general public soon changed its opinion. Experiments of that nature on humans fell out of fashion, with some even suggesting that they were satanic in nature. Ure continued to lecture about his experience with galvanization, though, long after that day in 1818.