The London Beer Flood

Join us at the Haunted Palace Blog as we investigate the Great London Beer Flood.

In 1814 England had a lot to deal with. The king, George III, was incurably mad; England was at war, not just with the French, in the ongoing Napoleonic Wars, but with erstwhile colony, North America, in what was to become known as the War of 1812.

It was also a cold year, a disappointing summer was followed by bitter winter, cold enough for a Frost Fair on the River Thames, the very last one, as it turns out.

1814 was also the year of one of the most bizarre disasters in English history, one that is now all but forgotten.

This is the story of the London Beer Flood of 1814.

By Richard Horwood, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

St Giles Rookery

In the seventeenth century, the wealthy Bainbridge family owned land in the Parish of St Giles, West London. Over time, they gradually leased it all out to landlords, who, greedy for profit, built fast and cheap. The result was a warren of dark alleyways and dingy courts leading to masses of cheap lodging houses. Over the course of the eighteenth century, these densely packed dwellings fell into disrepair and disrepute. The St Giles Rookery, as it became known, soon became one of the most notorious areas of slum housing in London. Its inhabitants were made up of the lowest rung of society: impoverished families, the unemployed, criminals. Many were Irish immigrants and were treated with suspicion and distain by Londoners.

Within these multiple occupancy houses, people were crammed in everywhere, from drafty garret to dank cellar and every space between. People lived in corridors, on landings, in kitchens, sometimes several families shared a single room. It was, to say the least, a hard life. But children still played, and families still loved each other, and hoped for a better future.

Domestic scenes

At tea-time on Monday 17 October 1814, the inhabitants of St Giles Rookery went about their daily lives, unaware of the disaster about to engulf them.

On New Street, Mrs Banfield was sitting down to tea with her 4-year-old daughter Hannah and another child.

In a nearby cellar dwelling, a party of Irish immigrants met. Anne Saville had tragically lost her 2-year-old-son John and was holding a wake for him. She was joined by a thirty strong gathering, including Elizabeth Smith, Catherine Butler and Mary Mulvaney, Mary had also brought along her own 3-year-old son, Thomas. Perhaps the children had been playfellows.

Not far away, 3-year-old Sarah Bates was playing in her room.

Over on Old Russell Street, at the Tavistock Arms, 14-year-old Eleanor Cooper was hard at work in the back yard of the pub, scrubbing pots.

Messer’s Henry Meux & Co Horseshoe Brewery

Messer’s Henry Meux & Co owned the Horseshoe Brewery on Bainbridge Street (on the corner of Great Russell Street and Tottenham Court Road). They were one of Britain’s most prolific producers of Porter, a thick dark beer that was popular at the time, producing upwards of 100,000 barrels of beer a year.1

The Brewery backed onto New Street, George Street, and was close by Great Russell Street (see map above).

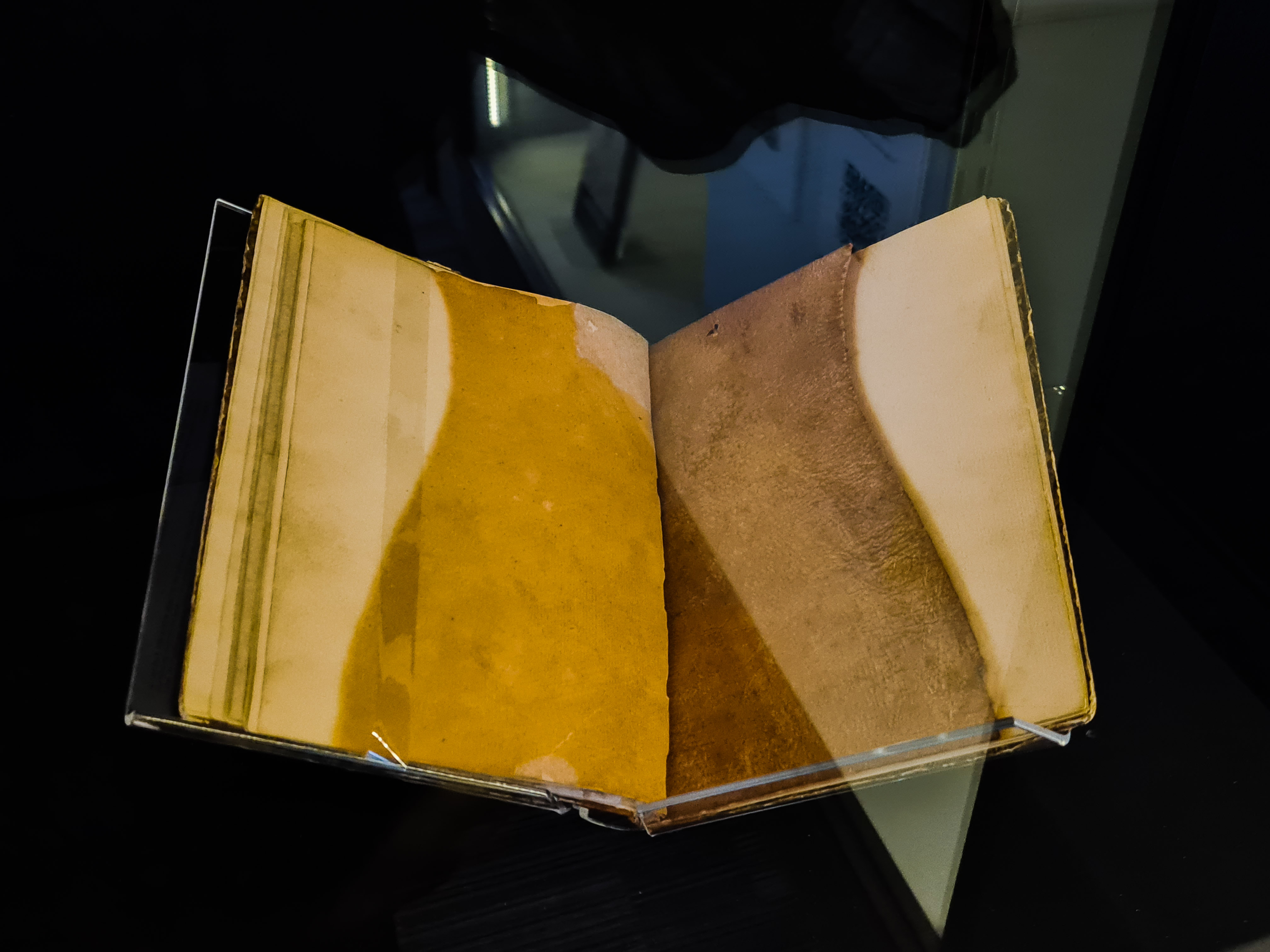

The Brewery storehouse contained rack upon rack of huge wooden vats of fermenting Porter, each bound by several heavy iron hoops. The scale is not to be underestimated, the vats stood 22ft (6.7m) tall and some of the hoops weighed up to a tonne in weight. When full the vats contained around 3,555 barrels2 of beer (upwards of 500,000 litres of beer).

On Monday 17 October, at around 4.30pm, Mr George Crick, the storehouse manager carried out an inspection. He quickly noticed that one of the vats had a problem. One of the iron hoops had fallen down. He was not unduly alarmed as hoops slipping was quite a common occurrence. He informed his manager, then left the storeroom to write a note to Mr Young, a partner in the business and the man tasked with building and repairing the vats.

At around 5.30pm, as Mr Crick stood, letter in hand, in a nearby room, he heard a huge crash. Rushing back into the storeroom, he was horrified to see that the vat had burst, not only this, but the force of the eruption had demolished the 25ft (7.6m) high brewery wall and most of the roof in the process. To make matters worse, he saw the body of the superintendent of the storehouse, his own brother, lying motionless in the rubble, along with many other injured workers.

This was only the beginning of the horror. Along with a rain of bricks and rubble that fell upon nearby New Street, demolishing two houses outright, the burst vat had released a tidal wave of beer. It is estimated that between 580,000-1,470,000 litres of beer flooded out of the Horseshoe Brewery, surging down the neighbouring streets in a fifteen foot (4.6m) high tidal wave of beer.3

It was heading straight for the St Giles Rookery.

Dreadful Accident

The rescue effort began quickly, with people wading waste deep through beer to search for survivors. The terrible effect of the catastrophe was palpable, injured, and distressed people filled the streets, crying, and desperately picking through the rubble for their loved ones, straining to hear the faint cries of those still trapped.

Much of what we know about the disaster comes from the witness statements taken at the Coroner’s Inquest.

Mr Cummins lived in Camden Town, but he also owned a house on New Street, and he spent most of Tuesday 18 October there, helping recover the bodies.

The first body he found drowned was that of Elizabeth Smith, the wife of a bricklayer, one of the guests at the wake. An hour later, at Number 3, he found the lifeless body of little Sarah Bates.

By 4pm Mr Cummins entered the cellar where the wake had taken place and found the body of the grieving mother, Mrs Savill, floating amongst the butts in the cellar. Four of her guests, including Mrs Mulvaney and her three-year-old son, Thomas, also perished when the cellar was inundated with beer. They never stood a chance.

Mrs Banfield, who had been in the middle of having tea with her daughter and another child, found herself caught up in a terrifying tide of beer which swept her off her feet and out of a window, leaving her battered and bruised on the street outside. Amazingly, she survived this ordeal. The other child was later found almost suffocated on a bed, she too survived.

Poor little Hannah was not so lucky –

“The daughter was swept away by the current through a partition and dashed to pieces” 4

Her body was recovered at 6.30pm.

Teenage Eleanor, cleaning her pots in the backyard of the Tavistock Arms on Great Russell Street, found herself instantly buried beneath a collapsed wall. It took Mr Howse, the landlord, until twenty past eight that night to dig her out of the rubble.

“She was found standing by the water butt, quite dead” 4

She had suffocated.

Others, upon finding their dwellings suddenly inundated, desperately climbed on top of their highest furniture until the flood subsided.

The situation was aggravated because the land around the brewery was flat and had little drainage, so the beer did not flow away, instead it spread out in the neighbouring streets, filling up cellars first, then ground floor rooms, as it went.

The Aftermath

It was initially feared that the death toll would be huge because almost every inundated cellar in St Giles was inhabited. However, once the flood had subsided, and the bodies were counted, it was found that in total eight people had perished. Most of them women and children who had been either caught unawares or trapped by the flood.

The victims were named at the Inquest:

- Eleanor Cooper, age 14

- Mary Mulvaney, age 30

- Thomas Murry, age 3 (Mary Mulvaney’s son)

- Hannah Banfield, age 4 years 4 months

- Sarah Bates, age 3 years 5 months

- Ann Saville, age 60

- Elizabeth Smith, age 27

- Catherine Butler, age 65

Many more were injured, including thirty-one workers at the Brewery (although almost unbelievably, despite their proximity to the disaster, none of the workers perished). The injured, including Mrs Banfield, were taken to Middlesex Hospital.

The bodies of the dead were sent to the St Giles Workhouse and an Inquest was held on 19th October 1814.

Mr Crick, the storehouse clerk at the Brewery, Mr Howse the landlord of the Tavistock Arms, Mr Cummins, and others, gave their witness statements to the Inquest.

As part of the investigation, witnesses were also taken back to the site of the incident to view the destruction. By now, vast crowds of onlookers had also arrived to view the scene of the flood. Warehouse workers at the brewery even began charging visitors to see the ruins of the storeroom.5

It is often claimed, even today, that relatives charged visitors to view the bodies of the dead, and that so many piled into to the building where the corpses were displayed that the floor collapsed, depositing these dark tourists into the beer-filled cellar beneath. While viewing corpses was certainly a popular tourist attraction in the nineteenth century (Brits travelling to Paris, flocked to the Paris Morgue considering it a a popular tourist attraction) there is no contemporary evidence that this happened following the Beer Flood.6

Inquest discovered that the flood had been exacerbated because:

“When the vat burst, the force and pressure was so great it stove several hogsheads of porter, it also knocked the cock out of a vat nearly as large…” 7

After hearing all of the evidence, the coroner’s verdict was that the victims’ deaths were not the fault of the brewery, but were caused “casually, accidentally, and by misfortune.” 8

Compensation

Today, victims of a tragedy like this might expect to receive compensation. However, the verdict of the Coroner’s Inquest, that the disaster was an unfortunate accident, meant no compensation was paid to the families of those who lost loved ones, or lost their homes and possessions in the flood.

Nevertheless, some indirect financial compensation was paid, just not to the victims. The disaster had cost Messer’s H Meux an estimated £23,000 (over £1,000,000 in today’s money. To avoid the company going bankrupt, the government agreed to refund the excise tax that the company had paid in advance, and paid the company £7250 (around £400,000) compensation for their lost beer.9

I can’t help thinking that this must have been a bitter pill to swallow for those who lost their lives, their family members, and all their possessions, in the Beer Flood.

Despite the lack of help from the government, compassion was not entirely lacking. Many curious Londoners who flocked to the area, as people inevitably do when disaster strikes, found themselves filing past the coffins of the victims. Many were moved by the loss they saw. And while most of them were themselves poor, they contributed their pennies, sixpences, and shillings, to ensure that the victims could be properly laid to rest.

Did the poor get drunk in the streets?

There was a persistent rumour that in the days after the flood, the locals took advantage of the rivers of beer flowing in the streets and got outrageously drunk and rowdy. It was even said that some people drank themselves to death as a result.10

However, the idea of mass public drunkenness following the flood has been challenged by Martyn Cornell. The affected area was home to a large immigrant Irish population which was often treated with distain and unease by Londoners. Cornell points out that there were no contemporary newspaper reports of this type of behaviour, and it is unlikely the press would have missed a chance to lambast Irish immigrants or the undeserving poor.11

Conclusion

The idea of a beer flood, on the surface sounds quite entertaining, conjuring up images of boozy Londoners partying in the streets while guzzling free liquor. However, the devastation and personal tragedies caused by this sudden and catastrophic event must have been terrible for those affected.

It may well be that the idea of the London Beer Flood being a huge drunken street party grew up later on, when details of the actual events had faded from memory, allowing the story to transform into just one more bizarre and amusing anecdote from London’s long and eventful history.

H Meux & Co’s Horseshoe Brewery is long gone, the site now occupied by the Dominion Theatre.

Sources

The Great London Beer Flood was reported widely by the contemporary press. Details of events and the Coroner’s Inquest findings came from the following newspapers, but many more reported the event.

Hampshire Chronicle – Monday 24 October 1814

Leeds Mercury – Saturday 22 October 1814

The Scots Magazine – Tuesday 01 November 1814

The newspapers are available via www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Other Sources

Cornell, Martyn, https://zythophile.co.uk/2010/10/17/so-what-really-happened-on-october-17-1814/

Historic currency converter https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/

Johnson, Ben, The London Beer Flood of 1814 https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-London-Beer-Flood-of-1814/

Klein, Christopher, The London Beer Flood https://www.history.com/news/london-beer-flood (MAY 10, 2023 | ORIGINAL: OCTOBER 17, 2014)

London Beer Flood https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Beer_Flood

Weather reports for 1814: https://www.pascalbonenfant.com/18c/geography/weather.html

Notes

- Christopher Klein, The London Beer Flood

- Wikipedia, London Beer Flood

- Martyn Cornell, What really Happened on October 17 1814?

- The Scots Magazine, Tuesday 1 November 1814

- Christopher Klein, The London Beer Flood

- Martyn Cornell, What really Happened on October 17 1814?

- The Scots Magazine, Tuesday 1 November 1814

- ibid

- Christopher Klein, The London Beer Flood

- Ben Johnson, The London Beer Flood of 1814

- Martyn Cornell, What really Happened on October 17 1814?

Leave a Reply